by Gui Andrade

by Gui Andrade

Let's say you're one of the paranoid types. Maybe you're convinced North Korean agents are out to steal your secrets. Anyway, you want to make sure your computer data is secure from your potentially evil maid while you're out walking your dog at the park every day.

So you encrypt your hard drive and get on with your life. Nobody can steal your secrets if they can't read your secrets.

Turns out, if you're running any sort of normal consumer PC, your hard drive has a section at the very beginning, either the Master Boot Record or the GUID Partition Table, that does some bookkeeping for your hard drive. These sections aren't encrypted, and so an evil maid could read them, change a value, and have your computer boot up to a completely different operating system the next time you open it.

Just for fun, your evil maid had the following scheme:

Wow, that's a contrived scheme! Right out of a heist movie, I'd say. And yeah, if you were already that paranoid you'd probably at least have Secure Boot enabled (although every once in a while researchers figure out how to bypass it, sometimes in amazing ways). And of course, the maid could bug your computer some other way or hold a gun to your head until you tell them your password.

But that's not the point.

I want to think about a scheme where you can trust this hard drive we left laying around for tampering hands to access. Unfortunately, it's going to require you to wear a flash drive necklace. Sorry!

For this to work, you need to have something that you can absolutely trust. It's with you at all times; it never leaves your person; like Frodo, it's your burden to carry, and you'll carry it around your neck.

You don't want something super obtrusive, so this flash drive isn't going to be one of those giant industrial ones. It'll be small, dainty, stylish even, and that means it won't fit very much data on there. So we'll have to be frugal with our bytes.

This flash drive will have three crucial things on it:

And with those three things, we've exhausted the storage space on our drive. I told you it would be minimal! Also that last one sounds a little mysterious. We'll investigate more.

Hash functions are incredibly useful mathematical tools that takes in a number as input, and spits out a number as output. The input can be as big as you possibly desire, but the output will always be N digits long. Oh, and one more thing: for a good hash function, it's very hard to find two inputs that result in the same output (billions of computer years hard).

So there we go! If we take our whole hard drive contents, encode it as a number, and run it through a hash function, we can obtain a fingerprint of the contents of our hard drive. And we can be overwhelmingly confident that if:

And that means that every time we boot up our OS, we can just take a hash of the hard drive and compare it to the one we stored on the flash drive. Easy! Maid thwarted.

But wait, let's say you have some super fancy 1TB SSD. You have to hash it all when you boot. It's max speed is 3.5GB/s. Just to read out its contents will take some 5 minutes, every boot! But it gets worse. When you write to the hard drive, you have to update the hash so you can check against it later. If you're lucky, you could get away with doing that when you power off (and suffer 5 minute power off times). But if the power cuts out? You've lost all notion of what data is safe. Besides, your CPU will run HOT the whole time. Better not be running off a battery!

Okay, instead of hashing everything all at once, we're going to taking things piece by piece. Let's define some block size -- I'll use 1MiB -- and split up our 1TB drive into about a million of these blocks.

Now, instead of hashing the entire hard drive all at once, we'll hash individual blocks. We'll also keep all these block hashes stored on disk, which is going to consume about 32MB of our 1TB space.

Every time we read from the disk, we read the whole block, hash it, and check the hash against the store. Every time we write to the disk, we hash the block, and overwrite the hash in the store.

There's one more thing: how do you trust that your maid didn't just change one of the hashes on disk? To solve that problem, we'll have to compute a hash over the whole on-disk hash store, too. This is going to be your root hash that you keep safe around your neck. You check against it with every read or write, and update it with every write.

So instead of greedily computing the whole disk hash, we're lazily computing much smaller block hashes as we need them. This hugely cuts the latency of hashing, but we paid a space penalty of 32MB to pull it off.

Even though we've improved our implementation by quite a bit, we can do better. Each load/store we're still hashing the 1MiB original block as well as the entire 32MB hash store! Not only is that incredibly lopsided, but it's still too much hashing overhead.

As a first step, let's cut our overhead almost in half. We'll take our 1 million hashes on disk, and split them up into 2 different stores of 500 thousand hashes each. A store or load will hash the 1MiB block, and one of the 16MB on-disk stores. And then... well, now we have two root hashes instead of one. But we can take two hashes and just hash them together! And now we have a single root hash. Now each load/store is hashing only 17MB, down from 33MB.

If we add another 2-way split, we've cut down to 9MB. Another, and it's 5MB. Turns out that if we repeat this process as far as we can, we'll only be hashing the 1MiB block, plus 32B*log2(1,000,000 blocks). Or about 1.0006MiB. So basically we're only hashing that data block with some straggler data on the side. All these intermediate hashes we're doing, and storing, take up a little bit of disk space, but not too much: about 32B*1,000,000 blocks. So we're using 64MB total disk space now to store hashes.

We can adjust the block size and try to decrease runtime overhead even more, at the cost of extra disk space for the hashes. With 1KiB blocks, we'll need about a billion of them. Total disk overhead for hashes will be about 64GB. But each read/write will only need to hash 1KiB + 32B*log2(1 billion blocks), or a meager 2KB. 500 times fewer bytes hashed per access!

The multilayered hashing we do above, it turns out, implicitly denotes a tree (as you can see from the diagram). So we're going to make it explicit. In order to check the integrity of your hard drive, you need to store an integrity tree somewhere on disk. Here we converged on a binary search tree, but you may want to experiment with using other kinds of trees (like B-trees) and measure how performance changes.

Warning: I'm not a kernel developer, so I'm going to have to speculate a bit as to how one might actually implement this.

But I'd imagine one would add an extension to the MBR or GPT header at the first block of the hard drive. You'd store the block size there, and find somewhere to flag that the system is dealing with a hashed disk. The block size, and disk size, would determine the size of a hidden hash tree partition at the end of the disk. You'd also modify the kernel to detect the hashed disk, and you'd hook the block read/write functions to perform hashing and update the hash tree partition. And as necessary, you'd update the root key, which you might store somewhere on the boot partition (since we're using a flash drive, that's where we expect the boot partition to be) and disallow usermode writes to this file. If the kernel detects a hash mismatch, it could return an error as if it had run into a bad disk block.

This post has been motivated by, and indeed essentially describes through allegory, my work with the UC Berkeley ADEPT Lab on the Keystone Trusted Execution Environment framework for RISC-V.

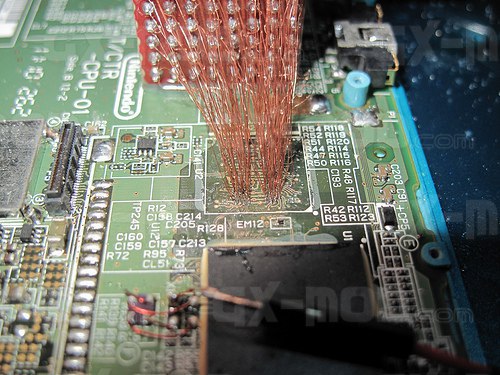

In the scheme here, we have two security domains: hard drive (insecure) and flash drive / RAM (secure). In Keystone, we also have two security domains: off-chip memory / storage (insecure) and on-chip memory (secure). We presume an attacker is unable to access any ROM or SRAM inside the physical SoC package where we're running. But any traces leaving the chip are considered potentially compromised. This includes the system's main memory. For a fun example of how you can compromise main memory, check out neimod's attack on the 3DS. Real dedication!

Since we consider any off-chip data insecure, it makes sense to implement encryption and integrity protection for any Secure Enclave data that doesn't fit on the (very small) on-chip memory.